RECIPROCAL INHIBITION MUSCLE ENERGY TECHNIQUE Vs STRETCHING IN PIRIFORMIS SYNDROME: A RANDOMIZED EXPERIMENTAL STUDY : Krishna Kumar Singh* Shekhar Singh **

Introduction:

Low back pain a common disabling condition in present days. Many patients with piriformis syndrome present with low back pain, so a skilled clinician is important to distinguish piriformis syndrome from other causes of lo-backache. Piriformis syndrome can be managed effectively by conservative means such as NSAID, spasm relief medications and physiotherapeutic such as stretching exercises, US therapy, TENS etc.

Objective:

To compare effectiveness of PIR and the conventional stretching exercises after application of hot packs on functional outcomes. Materialandmethods: 30 subjects with back pain, reporting to P.T. Department, were evaluated for piriformis syndrome and were grouped in Group–A (Experimental Group) and Group-B (Control Group) randomly. Patients were selected on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria’s and their base line data with respect to age, gender and hip internal rotation range of movement by goniometer, pain in VAS and disability level by MODQ were noted. After 10 days of intervention hip internal rotation range of movement, pain in VAS and disability level by MODQ was noted.

Date Analysis:

It was carried out by using Mann-Whitney’s u’test for subjectively assessed data and unpaired ‘T’ test for objectively assessed data, with 95% confidence interval.

Results:

The subjects treated with PIR (MET) with piriformis syndrome that is experimental group (Group-A) showed a statistically significant decrease in pain (P=0.000), amount of hip internal rotation restriction (P=0.000) and disability level according to MODQ (P=0.000) after 10 days of intervention as compared to the control Group (Group-B) that received conventional stretching exercises only.

Conclusion:

Both groups showed improvement following 10 days of treatment but experimental group (Group-A) showed a significant decrease in pain, amount of hip internal rotation restriction in degrees and disability level as per MODQ following application of PIR (MET) compared to control Group (Group-B) conventional stretching exercises for piriformis syndrome.

Key words: Piriformis syndrome, post-isomeric relaxation technique, muscle energy technique, manual therapy, stretching exercise.

INTRODUCTION

Piriformis syndrome (PS) is a condition in which the piriformis muscle becomes tight or has spasm and irritates the sciatic nerve. This causes pain in the buttocks region and may even result in referred pain in the lower back and thigh. Patients often complain of pain deep within the hip and buttock and for this reason, piriformis syndrome has also been referred as “Deep Buttock Syndrome”.

Piriformis syndrome is predominantly caused by a shortening or tightening of the piriformis muscle, and while many things can be attributed to this, they can all be categorized into two main groups: Overload (or training errors) and Biomechanical Inefficiency.

Yeoman, based on the intimate anatomic relationship of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ), the piriformis muscle (PM) and the sciatic nerve, reported that sciatica may be caused by a so called “periarthritis” involving the anterior sacroiliac ligament, the PM and the adjacent branches of the sciatic nerve 2.

In 1938 Beaton and Anson3 examined 240 human cadavers, they described six variations of sciatic nerve exit and considered that the close relationship of the piriformis muscle and the nerve affects the latter in cases of muscle infection or generally in cases of muscle spasm, specified when the PM is pierced by the nerve.

Commonly muscles covering posterior aspects of the hip joint form two layers i.e. outer layer consists of gluteus maximus and tensor fasciae latae, while inner layer consists of short external rotators of hip such as piriformis, superior gemellus, obturator internus, inferior gemellus and the quadratus femoris. The piriformis is the abductor and external rotator of the hip and is a flexor of the hip in walking. It rises from the pedicles of the II,III and IVsacral vertebrae and adjacent portion of the bone lateral to the sacral foramina the muscle passes the greater sciatic foramen and coursing laterally is inserted by a round tendon into the superior border of the greater trochanter. So it is in contact with the anterior ligament of the sacroiliac joint and the root of the first, second and third sacral nerves. Its lower border is closely related to the whole of the sciatic nerve 4 elements 1985 .

Although the syndrome was described originally in 19455, there was no universal agreement about its diagnosis and treatment, thus affecting epidemiologic 1 analysis .

Bernard et al6 in their review of 1293 patients referred to their clinic with low back pain, cited an incidence of 0.33% for piriformis syndrome. While pace and Nagle7 reported 45 patients with piriformis syndrome gleaned from 750 patients with an incidence of 6.1 and female to male ratio was 6 to 1.

The literature reveals that piriformis syndrome is more often encountered in patients 30 to 40 years old 3 and sporadically in patients younger than 20 years. Robinson has been credited with introducing the term 5 “piriformis syndrome” in 1947 .

He stated that sciatica is a symptom and not a disease, because it is seldom caused by a primary neuritis, and he defined that the term piriformis syndrome should be applied to the type of sciatica that is caused by an abnormal condition of the piriformis 5 muscle that is usually traumatic in origin.

He stated that piriformis muscle and fascia become compressed between the swollen muscle fiber and the bony pelvis, leading to an

entrapment neuropathy. He also found that the piriformis was stretched after a few degree of leg raising. So that with muscular spasm or inflammation, the sciatic nerve may be directly compressed by the piriformis muscle.

The etiology of this syndrome is thought to be injury of the piriformis muscle resulting in spasm, edema and contractures of the muscle and subsequent 4 compression and entrapment of sciatic nerve . Yeoman (1928) stated that any lesion of the SI joint may cause inflammatory reaction of the piriformis muscle and its fascia4. The other possible causes of piriformis syndrome are-a history of blunt trauma in the gluteal region such as fall, activities that increases activities of hip rotators (constrictions of hip rotators.), prolonged sitting on hard surfaces, idiopathic, pregnancy unusual overload of the muscle which may be caused by attempting to refrain from a fall, surgery due to rough handling during anesthesia, extreme unusual positioning of the hips or prolonged weight bearing on the buttocks during the surgical procedure.

The common features of piriformis syndrome are:

1. Patient complains of buttock pain with or without leg pain which is aggravated by sitting or activities of the lower extremities.

2. Buttock tenderness extending from the sacrum to the greater trochanter, piriformis muscle tenderness on palpation or rectal or pelvic examination and aggravation of symptoms by hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation in the absence of low back or hip pathologies showing:-

1. Leg length discrepancy.

2. Weak hip abductors.

3. Pain on resisted abduction in the sitting position.

4. Pain when rising from a sitting position.

5. Patient present with dyspareunia and also rectal pain exacerbated by bowel movements because of the location of the piriformis muscle deep in the pelvic floor.

6. Pain in the inguinal area.

7. Sciatic pain associated with piriformis shortness, straight leg raising reproducing the pain, while external rotation of the relieves it, since this causes slackness of the piriformis.

Though that patient with piriformis syndrome may present with some or all of above clinical features, the following are considered as cardinal features or piriformis syndrome:-

1. A history of trauma to the sacroiliac and gluteal area.

2. Pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint, greater sciatic notch and piriformis muscle extending down to the leg and causing difficulty in walking.

3. Acute exacerbation of chronic pain brought on usually by stooping or lifting which can be greatly relieved by traction of the effected leg.

4. The presence of a palpable sausage shaped mass over the piriformis muscle during acute exacerbation of the pain and tenderness to pressure, is almost a pathologic sign,.

5. Apositive Lasegue’s sign.

6. Gluteal atrophy may be present depending on the duration of the conditions.

7. Pain and weakness on resisted abduction, external rotation of the thigh.

8. Pain on forced internal rotation of the extended thigh (+ve Freiberg s sign).

The clinicians considered different tests to come to a clinical diagnosis of piriformis syndrome. The most commonly used tests are- Freiberg’s sign, Pace sign, Beatty’s maneuver, Stretch test , Palpation test and SLR

With increasing knowledge of neurophysiology and its clinical implications in recent times, many physiotherapists are trying to take advantage of these in rehabilitation of patients. One among these is muscle energy technique (MET), where a physiotherapist uses different neuromuscular physiological principles in treatment of musculoskeletal disorders such as pain, muscle spasm and muscle shortening etc. This is again of various types such as isometric type or isotonic type or isokinetic type. One of the muscle energy technique (MET) that is post isometric relaxation (PIR) technique which works on neurophysiological principles, states that after a muscle is contracted, it is automatically in a relaxed state for a brief latent period. The effect of MET (PIR), which causes a sustained contraction on the Golgi tendon organs, seems pivotal. The responses to such a contraction seem to be to set the tendon and the muscle to a new length by inhibiting it.

Lewitt K, in 1984 had stated about usefulness of METin treatment of trigger points in the myofascial pain and found that MET is very effective in treating myofascial pain and restoring resting length of the 12 affected muscle.

However, there is hardly any study that could find out the effectiveness of MET in form of Post Isometric Relaxation (PIR) in piriformis syndrome especially after application of hot pack to piriformis muscle. As pain and spasm cycle is the major problem of the patient and therapist all efforts are being made to relieve patients discomforts by using most convenient and psychosomatically suitable therapeutics such as MET and hot packs.

Hot packs being a relatively superficial heating modality in comparison to other heating modalities with respect of depth of penetration, usually gets more absorbed in tissues with higher water content such as muscle. Thus, it increases local circulation and helps in relieving the local spasm and inflammatory process resolution in piriformis muscles. So, it is helpful in soft tissue stretching with minimal discomfort and reducing the signs and symptoms of piriformis syndrome.

This study was undertaken to find out the effectiveness of METin the form of PIR in the treatment of pirifomis syndrome flowing the application of hot pack to the piriformis muscle area considering the above neurophysiological principles of therapy.

Procedure

Subjects were recruited from Mahraj Vinayak General Hospital with back pain or pain in the hip, who reported to the physiotherapy department, were screened after finding their suitability as per in the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria’s and then they were requested to participate in the study. The subjects willing to participate in the study were briefed about the nature of the study and the interventions.

After briefing, their informed written consent was taken. Their demographic data were collected. Participating subjects were evaluated in detail for the study needs with special emphasis on three positive signs out of the tests such as Pace sign or Freiberg’s sign or Beatty maneuver or stretch test. The other areas assessed during this were for quantification of pain profile by using Visual analog scale, hip range of motion (internal rotation by goniometer, and disability level by Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (MODQ)).

After these, 30 subjects were allocated to two groups namely, experimental Group (Group-A) and Control Group (Group-B). Randomization was done by envelope method based on computer generated randomization list.

Tools Used :

-Modified Oswestry disability questionnaire (MODQ )

-Visual analog scale ( VAS )

-Goniometer

Inclusion Criteria :

-Age group- 30 to 50 years

-Subject with piriformis syndrome showing positive sign for the all special test

-Pain more than or equal to 4 in VAS.

-Subjects who are willing to participate.

Exclusion Criteria:

-Pain arising from Hip joint

-Pain due to Neurological and spinal origin

-Sacro-iliac dysfunction

-Fixed deformities of lower limb and spine

-Pain from pelvic origin

-Any disorder of lower limb that might warrant treatment.

Following this, all the subjects were positioned on prone lying comfortably. The affected side piriformis muscle area was palpated for tenderness and trigger point sand the whole muscle bulk was subjected to application of hot packs exposure for 20 minutes. Then the subjects of control group (group-B) were treated with conventional piriformis stretching for 20 seconds, repeated for 5 times in each session.

Subjects in experimental group (group-A) were treated with PIR (MET) for 20 seconds along with above common regime of treatment and it was repeated for five times per session. This method is based on the test position for shortened piriformis muscle described by Lewit. Here the patient remains in supine position, the treated leg is placed into flexion at the hip and knee, so that the foot rests on the table lateral to the contra lateral knee .The leg on the side to be treated is crossed over the other straight leg.

The angle of hip flexion should not exceed 60 degrees. The practitioner places opposite hand on the contra lateral ASIS to prevent pelvic motion, while the other hand is placed against the lateral aspect of the flexed knee, as this is pushed in to resisted abduction to contract piriformis for 20 seconds. Following the contraction, the practitioner eases the treated side leg in to adduction until a sense of resistance is noted; this is held for 20 seconds and repeated for 5 times per session for 10 days.

At the end of 10 days of treatments, pain in visual analog scale, hip range of motion (internal rotation) and disability level as per MODQ were assessed and noted.

Statistical Analysis And Results:

The details of the participants with respect to age, gender VAS score, and Hip IR range of motion and level of disability as per MODQ were noted prior to intervention as base line data. After 10 days of regular physiotherapy interventions, VAS score, Hip IR range of motion and level of disability as per MODQ were noted. The statistical analysis for above two groups were performed to find out mean, SD and the statistical significance between PIR and conventional stretching exercises following application of hot packs to both groups having piriformis syndrome. The sex ratio of two groups was analyzed by chi-square test with Yates correction. Baseline features were compared between groups using the unpaired’t’ test for continuous data. Inter group comparisons between the groups were also achieved with the unpaired’t’ test. Mann Whitney ‘U’ test was carried out for subjectively assessed data such as VAS score and MODQ values. The statistical analysis was conducted at a 95% confidence level and a P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

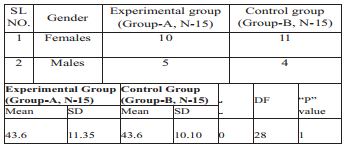

The mean age of control group was 43.6 years with standard deviation 10.10 years, age ranging from 34 to 60 years and that of experimental group was 43.6 years with standard deviation of 11.35 years, age ranging from 22 to 60 years respectively. The difference in mean age of two groups was not statistically significant (“t”-0 and “p” value=1).

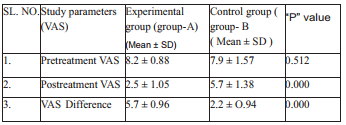

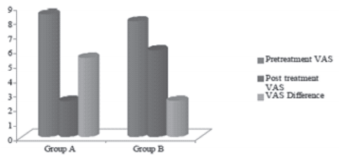

Visual Analogue Scale Analysis

The mean and SD values of pre-intervention stage VAS for group-Aand group-B were 8.2 + 0.88 and 7.9 + 1.57 respectively. The VAS difference between two groups were not statistically significant during pretreatment stage (P=0.512).

While the mean and SD values of VAS in post treatment stage for group – Aand group-B were2.5 +1.05 and 5.7 + 1.38 respectively, the group-A demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in pain comparing to group-B (P=0.000). As far mean and SDs of VAS difference between pre and post treatments phases are concerned for two groups, they were 5.7 + 0.96 for group – Aand 2.2 + 0.94 for group -B respectively. There was a statistically significant reduction in VAS score in groupAcomparing to group-B (P=0.000).

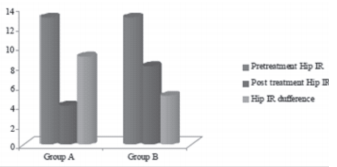

Hip Internal Rotation Range of Motion Analysis (in Degree):

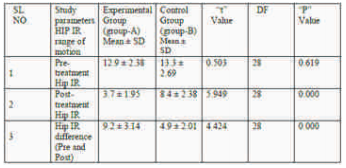

The mean and SDs values of pre-intervention stage hip internal range of motion for group-A and group-B were 12.9 + 2.38 and 13.3 + 2.69 respectively. The difference of degrees of hip internal rotation restriction between two groups was not statically significant during pre-treatment stage (“t” = 0.503 and “p” = 0.619).

While the mean and SDs values of post-treatment study of hip internal rotation range of m o t i o n f o r group-A and group-B were 3.7 + 1.95 and 8.4 + 2.38 respectively. The group A demonstrated a statistically significant decreases in Hip IR range of motion restriction comparing to group-B during post treatment stage (“t” = 5.949 and “p” = 0.0.00).

As far as mean and SDs values of hip internal rotation range of motion restriction difference between pre and post treatment stages are concerned for two groups. They were of 9.2 + 3.14 for group – A and 4.9 + 2.01 for group-B respectively. There was a statistically significant decrease in hip IR range of motion restriction in group-A comparing to group-B during post treatment stage (i.e. “t” = 4.424 and “p” = 0.0.00).

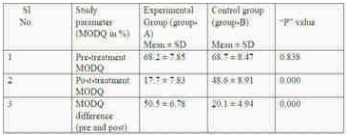

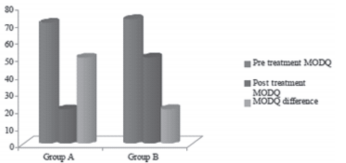

Disability Level (As per MODQ) Analysis (In percentage): The mean and SD values of preintervention stage disability level as per MODQ for group-A and group-B were 68.2 + 7.85 and 68.7 + 8.47 respectively. The difference of disability level between two groups was not statistically significant (P=0.838).

While the mean and SD values of post treatment stage disability level as per MODQ for group-A and group-B were 17.7 + 7.83 and 48.6 + 8.91 respectively. There was a statistically significant reduction in disability level in group-A comparing to group-B (P=0.000).

DISCUSSION

The statistically significant decrease in pain in VAS seen in experimental group could be attributed to physiological and therapeutic effects of hot packs and MET (PIR). Hot packs usually gets absorbed more in tissues with high fluid content especially muscle.

Piriformis muscle being a deep seated muscle must have got adequate heating effects, which could have reduced chronic inflammatory process and subsequently has reduced spasm and increased flexibility of this muscle. While application of PIR must have further facilitated the resolution of chronic inflammatory lesions and spasm of the piriformis muscle due to its effects similar to the soft tissue techniques such as stretching of soft tissue in affected area, moving of fluids out of inflamed area and reflexly relaxing muscles13 . The MET must have also health in restoring normal resting length of affected piriformis muscle due to its effect of restoring integrity of the myotonic stabilizing system (at least temporarily13).

Again its is thought the suprasegmental system as well as the muscle spindle receptors are reprogrammed by MET46. MET (PIR) to Piriformis muscle must have restored its near normal functional strength due to reduction in muscle inhibitions and increased its flexibility with respect to day to day requirements.

Due to above change, MET (PIR) must have also restored sacral torsion “as per muscle energy model” during walking where piriformis muscle plays a greater roel13 ,thus, allowing normal alignment in lumbopelvic sacral hip complex during walking and other activities of day to day life. Therefore subjects in experimental group have shown a statistically significant increase in hip internal rotation range of movement and also decrease in disability level as per MODQ.

Lewit K et al in 198412 in their study, had found that MET (PIR) when applied while the muscle is in a stretched position, produced greater relief in pain, spasm and tenderness in the affected muscle.

Probably all the above effect of MET have helped in resolution of pathological changes of piriformis muscle and decrease stress on the sciatic nerve by piriformis muscle.Thus, the subjects in experimental group that is who received MET, had shown statistically significant decrease of pain in VAS, increase in hip internal rotation range of motion decrease in disability level as per MODQ.

Control Group (Group-B) showed some improvements with respect to study parameters but the same was not statistically significant because hot packs and stretching exercises of piriformis muscle alone must not have contributed much to normal alignment of spine, sacrum, pelvis and hip. At the same time, it must have contributed to increase inflexibility of piriformis muscle. Thus, there was not much improvement in symptomatology of the patients in the Control Group (Group-B).

Limitations

1. Short duration study: The study was carried out only for 10 days, which was not sufficient to bring out a significant change especially in control group.

2. Small sample size: Though the study showed a statistically significant improvement in patients treating with PIR but a larger group study is necessary for further reinforcement of this study.

3. Follow up: There was no follow up of case after 10 days of treatment.

Further Recommendations

The suggestions for further studied are as follows:

1. The study should include a large group.

2. The study should be carried out for more than 10 days.

3. The study should include follow up for standardization of PIR in piriformis syndrome.

Conclusion

On the basis of result of this study it can be conducted that post isometric relaxation technique of MET is an effective physiotherapeutic intervention along with hot pack for pain relief, and decreasing in disability in patients who are suffering from piriformis syndrome?

References

1. Silver JK, Leadbetter WB. Piriformis syndrome: assessment of current practice and literature review (see comments). Orthopedics 1998;21:1133-5.

2. Yeoman W. The relation of arthritis of the sacroiliac joint to sciatica, with an analysis of 100 cases. Lancet 1928; 2: 1119-22.

3. Beaton LE, Anson B. The sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle; their interrelation a possible causes of coccygodynia. J Bone Joint Surge (Am) 1938; 20: 686-8.

4. Hui Wan Park, Jun Seop Jahina and Woo Hyeonglee, Piriformis syndrome case report. Yonsei Medical Journal 1991; 32: 1 64-68.

5. Robinson DR. Piriformis syndrome in relation to sciatic pain, Am J Surg 1947; 73:335-58.

6. Bernard Jr TN, Kikaldy – Willis WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain, Clin Ortho 1987; 217 : 266-80.

7. pace JB, Nagle D. Piriformis syndrome. West J Med 1976; 124: 435-9.

8. Beatty RA, The piriformis muscle syndrome- a single diagnostic maneuver, Neurosurgery, 194; 34(3) : 512-14.

9. Leon Chiatow. Muscle energy technique, 2nd edition, P.56, 109-113.

10. Carrie M. Hall and Lorithein Bordy. Therapeutic Exercise (Moving towards function): 2nd edition: P.481.

11. Leon Chaotow and Judith Walker Delany. Clinical Application of Neuro Muscular technique (Volume-2, the lower body), Churchill Livingstone Publication, China, P. 429-431.

12. Lewit K. Simons D. Myofascial pain relief by post isometric relazation. Arch phys med rehabil 1984 ; 65(8) : 452-6.

13. Freiberg AH, Vinke TH, Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint. J Bone joint Surg (Am) 1934; 16: 126-36.

14. JV Basmajian Rational Manual Therapy. Publisher Williams, P. 301-313.

15. Indrekwam K, Piriformis muscle syndrome in 19 patients treated by tenotomy – a 1-16 year follow up study. Int Orthop 2002; 26(2) : 101-3.

16. Justard ME. Piriformis syndrome. A rational approach to management of pain 1991; 9: 345- 52.

17. Pecina M. Contribution to the etiological explanation of the piriformis syndrome. Acta Anat (Based) 1979; 105:181-7.

18. Parizale JR et al. The piriformis syndrome. Am J Orthop 1996; (12: 819-23.